ROM cartridge

A ROM cartridge, usually referred to in context simply as a cartridge, cart, cassette, or card, is a replaceable part designed to be connected to a consumer electronics device such as a home computer, video game console or, to a lesser extent, electronic musical instruments.[1]

ROM cartridges allow users to rapidly load and access programs and data alongside a floppy drive in a home computer; in a video game console, the cartridges are standalone. At the time around their release, ROM cartridges provided security against unauthorised copying of software. However, the manufacturing of ROM cartridges was more expensive than floppy disks, and the storage capacity was smaller.[2] ROM cartridges and slots were also used for various hardware accessories and enhancements.

The widespread usage of the ROM cartridge in video gaming applications has led it to be often colloquially called a game cartridge.

History

[edit]

ROM cartridges were popularized by early home computers which featured a special bus port for the insertion of cartridges containing software in ROM. In most cases the designs were fairly crude, with the entire address and data buses exposed by the port and attached via an edge connector; the cartridge was memory mapped directly into the system's address space[4] such that the CPU could execute the program in place without having to first copy it into expensive RAM.

The Texas Instruments TI-59 family of programmable scientific calculators used interchangeable ROM cartridges that could be installed in a slot at the back of the calculator. The calculator came with a module that provides several standard mathematical functions including the solution of simultaneous equations. Other modules were specialized for financial calculations, or other subject areas, and even a "games" module. Modules were not user-programmable. The Hewlett-Packard HP-41C had expansion slots which could hold ROM memory as well as I/O expansion ports.

Computers using cartridges in addition to magnetic media are the VIC-20 and Commodore 64, MSX, Atari 8-bit computers,[5] TI-99/4A (where they were called Solid State Command Modules and were not directly mapped to the system bus) and IBM PCjr[6] (where the cartridge was mapped into BIOS space). Some arcade system boards, such as Capcom's CP System and SNK's Neo Geo, also used ROM cartridges. Cassettes and floppy disks cost less than ROM cartridges[citation needed] and some memory cards were sold as an inexpensive alternative to ROM cartridges.[7]

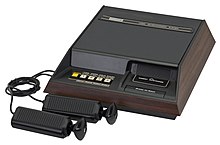

A precursor to modern game cartridges of second generation video consoles was introduced with the first generation video game console Magnavox Odyssey in 1972, using jumper cards to turn on and off certain electronics inside the console. A modern take on game cartridges was invented by Wallace Kirschner, Lawrence Haskel of Alpex Computer Corporation as well as Jerry Lawson at Fairchild Semiconductor, first unveiled as part of the Fairchild Channel F home console in 1976.[8][9] The cartridge approach gained more popularity with the Atari 2600 released the following year. From the late 1970s to mid-1990s, the majority of home video game systems were cartridge-based.[9]

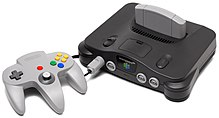

As compact disc technology came to be widely used for data storage, most hardware companies moved from cartridges to CD-based game systems. Nintendo remained the lone hold-out, using cartridges for their Nintendo 64 system; the company did not transition to optical media until the release of the GameCube in 2001.[10] Cartridges were also used for their handheld consoles, which are known as Game Cards in the DS/3DS line of handhelds. These cartridges are much smaller and thinner than previous cartridges, and use the more modern flash memory for game data rather than built-in ROM chips on PCBs for the same purpose.

The release of the Nintendo Switch in 2017 marked the company's shift away from their own proprietary optical disc-based media after last using them in the Wii U in favor of small cartridge-based media. These cartridges are known as Game Cards like previous Nintendo handhelds, and are much smaller and thinner than previous cartridges for consoles as well as Nintendo's own Game Cards for their DS/3DS handhelds. It uses a form of flash memory technology similar to that of SD cards with larger storage space. As of 2024[update], Nintendo is the only major company to exclusively use cartridges for their consoles and handhelds, as others such as Sony and Microsoft continue to use optical disc-based media for their consoles.

In 1976, 310,000 home video game cartridges were sold in the United States.[11] Between 1983 and 2013, a total of 2,910.72 million software cartridges had been sold for Nintendo consoles.[12]

Use in hardware enhancements

[edit]

ROM cartridges can not only carry software, but additional hardware expansions as well. Examples include various cartridge-based chips on the Super NES, the SVP chip in the Sega Genesis version of Virtua Racing,[13] and a chess module in the Magnavox Odyssey².[14]

Micro Machines 2 on the Genesis/Mega Drive used a custom "J-Cart" cartridge design by Codemasters which incorporated two additional gamepad ports. This allowed players to have up to four gamepads connected to the console without the need for an additional multi-controller adapter.[15]

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]

Storing software on ROM cartridges has a number of advantages over other methods of storage like floppy disks and optical media. As the ROM cartridge is memory mapped into the system's normal address space, software stored in the ROM can be read like normal memory and since the system does not have to transfer data from slower media, it allows for nearly instant load time and code execution. Software run directly from ROM typically uses less RAM, leaving memory free for other processes. While the standard size of optical media dictates a minimum size for devices which can read discs, ROM cartridges can be manufactured in different sizes, allowing for smaller devices like handheld game systems. ROM cartridges can be damaged, but they are generally more robust and resistant to damage than optical media; accumulation of dirt and dust on the cartridge contacts can cause problems, but cleaning the contacts with an isopropyl alcohol solution typically resolves the problems without risk of corrosion.[16]

ROM cartridges typically have less capacity than other media.[17] The PCjr-compatible version of Lotus 1-2-3 comes on two cartridges and a floppy disk.[18] ROM cartridges are typically more expensive to manufacture than discs, and storage space available on a cartridge is less than that of an optical disc like a DVD-ROM or CD-ROM. Techniques such as bank switching were employed to be able to use cartridges with a capacity higher than the amount of memory directly addressable by the processor. As video games became more complex (and the size of their code grew), software manufacturers began sacrificing the quick load times of ROM cartridges in favor of greater storage capacity and the lower cost of optical media.[19][20] Another source of pressure in this direction was that optical media could be manufactured in much smaller batches than cartridges; releasing a cartridge video game on the other hand inevitably includes the risk of producing thousands of unsold cartridges.[21]

Electronic musical instruments usage

[edit]Besides their prominent usage on video game consoles, ROM cartridges have also been used on a small number of electronic musical instruments, particularly electronic keyboards.

Yamaha has made several models with such features, with their DX synthesizer in the 1980s, such as the DX1, DX5 and DX7 and their PSR keyboard lineup in the mid-1990s, namely the PSR-320, PSR-420, PSR-520, PSR-620, PSR-330, PSR-530 and the PSR-6000. These keyboards use specialized cards known as Music Cartridges, a ROM cartridge simply containing MIDI data to be played on the keyboard as MIDI sequence or song data.[22][23]

Casio has also used similar cartridges known as ROM Pack in the 1980s, before Yamaha's Music Cartridge was introduced. Models that used these cartridges were in the Casiotone line of portable electronic keyboards.[24]

Cartridge-based video game consoles and home computers

[edit]

Blaze Entertainment

Fairchild Camera and Instrument

Interton

Nikko Europe

- NES/Famicom (with its clones like Terminator)

- SNES/Super Famicom

- Nintendo 64

- Game Boy

- Game Boy Color

- Game Boy Advance

- Virtual Boy

- Pokémon Mini

- SG-1000 Mark I / SG-1000 Mark II

- Master System / Mark III

- Genesis / Mega Drive

- Game Gear

- Pico

- 32X

- Genesis Nomad

- Advanced Pico Beena

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "CARTRIDGE | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". Dictionary.cambridge.org. May 25, 2022. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Novogrodsky, Seth (April 1984). "Plug in a Program". PC World. Vol. 2, no. 4. International Data Group. pp. 2–5. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ "Texas Instruments software catalog for TI-58C/TI-59" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ US patent 4485457A, Richard K. Balaska, Robert L. Hunter, and Scott S. Robinson, "Memory system including RAM and page switchable ROM", issued 1984-11-27, assigned to CBS Inc.

- ^ Pollson, Ken (October 30, 2008). "Chronology of the Commodore 64 Computer". Archived from the original on January 16, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ Hoffmann, Thomas V. (March 1984). "IBM PCjr". Creative Computing. 10 (3): 74. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ "What MSX? (GB)". February 11, 1984 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Edwards, Benj (January 22, 2015). "The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge". Fast Company. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "1976: Fairchild Channel F – First ROM Cartridge Video Game System". CED Magic. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ Kent, Steven (September 6, 2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: From Pong to Pokemon--The Story Behind the Craze That Touched Our Lives and Changed the World. Crown. pp. 450–453, 584. ISBN 978-0761536437.

- ^ "The Replay Years: Enter 1976". RePlay. Vol. 11, no. 2. November 1985. p. 150.

- ^ "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). Nintendo. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ Horowitz, Ken (March 17, 2006). "Sega's SVP Chip: The Road Not Taken?". SEGA-16. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ "C7010 Chess Module Service Manual". Manuals. Internet Archive. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "A Small History Of Micro Machines". Retro Gamer. No. 113. Bournemouth: Imagine Publishing. pp. 60–67. ISSN 1742-3155.

- ^ NES Cleaning Kit manual

- ^ Cook, Karen (March 6, 1984). "Jr. Sneaks PC into Home". PC Magazine. p. 35. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ Trivette, Donald B. (April 1985). "Lotus 1-2-3 For IBM PCjr". Compute!. p. 63. Archived from the original on December 20, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ "The SNES CD-ROM". Gamer's Graveyard. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ Isbister, Katherine (2006). "Interview: Ryoichi Hasegawa and Roppyaku Tsurumi of SCEJ". Better Game Characters by Design: A Psychological Approach. San Francisco, California: Elsevier Inc. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-55860-921-1. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ "Who You Pay to Play". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 82. Ziff Davis. May 1996. pp. 16–18.

- ^ Curtis, Jason (September 26, 2017). "Yamaha Music Cartridge". Museum of Obsolete Media. Archived from the original on March 16, 2023. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Jacob (November 5, 2020). "Yamaha DX Series". Perfect Circuit. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ^ "Casio ROM Packs". www.crumblenet.co.uk. Archived from the original on December 17, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

External links

[edit]- History of Home Video Games at the Wayback Machine (archived April 8, 2005)